Table Of Content

- Richard Neutra’s Architectural Vanishing Act

- A PROFESSIONAL, LICENSED AND INSURED CALIFORNIA ARCHITECTURAL AND INTERIOR DESIGN CORPORATION

- The Art of the Rope: How This Charro Completo is Preserving Trick Roping in the United States

- Wall Street rises to start a week full of earnings reports and a Fed meeting

- The Kaufmann Desert House by Richard Neutra

From an aesthetic point of view, they defined a clear plan, from a purely functional, serving as a shield against the wind. The desert, or rather, this primordial wilderness area that stretches around Palm Springs, fascinated Neutra. His 1927 book “Wie Baute Amerika” ends with images of houses of the Indian peoples of New Mexico and Arizona, praising their overlapping rooms, with terraces on the roof and the ability of mud brick to withstand inclement weather. Despite the neat precision of the Desert House, it evokes the spirit of the houses of those Indian tribes, which he admired so much. This vacation home was designed to emphasize the desert landscape and its harsh climate.

Richard Neutra’s Architectural Vanishing Act

His mode of ground-hugging modernism—with clean, cool lines that play off against the year-round California green—helped to define the local architectural vernacular. To give greater visibility to the renowned quality of “floating” in the design, the structural system combines wood and steel so that the amount of vertical supports necessary, limited in any case, is reduced. This is particularly evident in the living room, whose walls of steel and glass slide outward toward the southeast, while the construction of deck and supports the hanging wall sliding moving toward the pool and spatially linking the house with it. This radial arm became the hallmark of Neutra, is the “spider leg,” the umbilical cord that merges space and building.

A PROFESSIONAL, LICENSED AND INSURED CALIFORNIA ARCHITECTURAL AND INTERIOR DESIGN CORPORATION

A dialogue between indoors and outdoors is one of the Kaufmann Desert House’s finest attributes, lending it a cinematic quality. During the extensive renovation by Marmol Radziner in the 1990s, the original concrete and silica sand floors were patched. Neutra’s International Style architecture is heightened by the San Jacinto Mountains above.

The Art of the Rope: How This Charro Completo is Preserving Trick Roping in the United States

The house, which originally had 297 m2 in area, had been expanded to nearly 474 m2. The architects removed the areas added and restored the house based on the famous photographs Julius Shulman did of the house in 1947. The architects decided to also return to the desert garden look it had in times of Neutra.

The flow from interior to exterior space is not simply a spatial condition rather it is an issue of materiality that creates the sinuous experience. The glass and steel make the house light, airy, and open, but it is the use of stone that solidifies the houses contextual relationship. The light colored, dry set stone, what Neutra calls “Utah buff,” brings out the qualities of the glass and steel, but it also blends into the earthy tones of the surrounding landscape of the stone, mountains, and trees. A stunning concoction of glass, stone and steel, the home is made up of several wings that meet at the center. The floor plan emphasizes indoor-outdoor living, as almost every room opens to a scenic outdoor space.

The collaboration between the client and architect was grounded in a mutual appreciation for cutting-edge design and technological advancement, setting the stage for creating a landmark in modernist architecture. The Kaufmann House has gone through several owners after the Kaufmann’s owned the house, which led to the house to fall in disrepair and a lack of concern and preservation of the modern dwelling. However, a couple that appreciated 20th Century modern homes restored the house back to its original luster with the help of Julius Shulman. The Kaufmann House is now considered to be an architectural landmark and one of the most important houses in the 20th Century.

Palm Springs’ celebrity homes are a feast of desert drama - Sydney Morning Herald

Palm Springs’ celebrity homes are a feast of desert drama.

Posted: Thu, 14 Mar 2024 07:00:00 GMT [source]

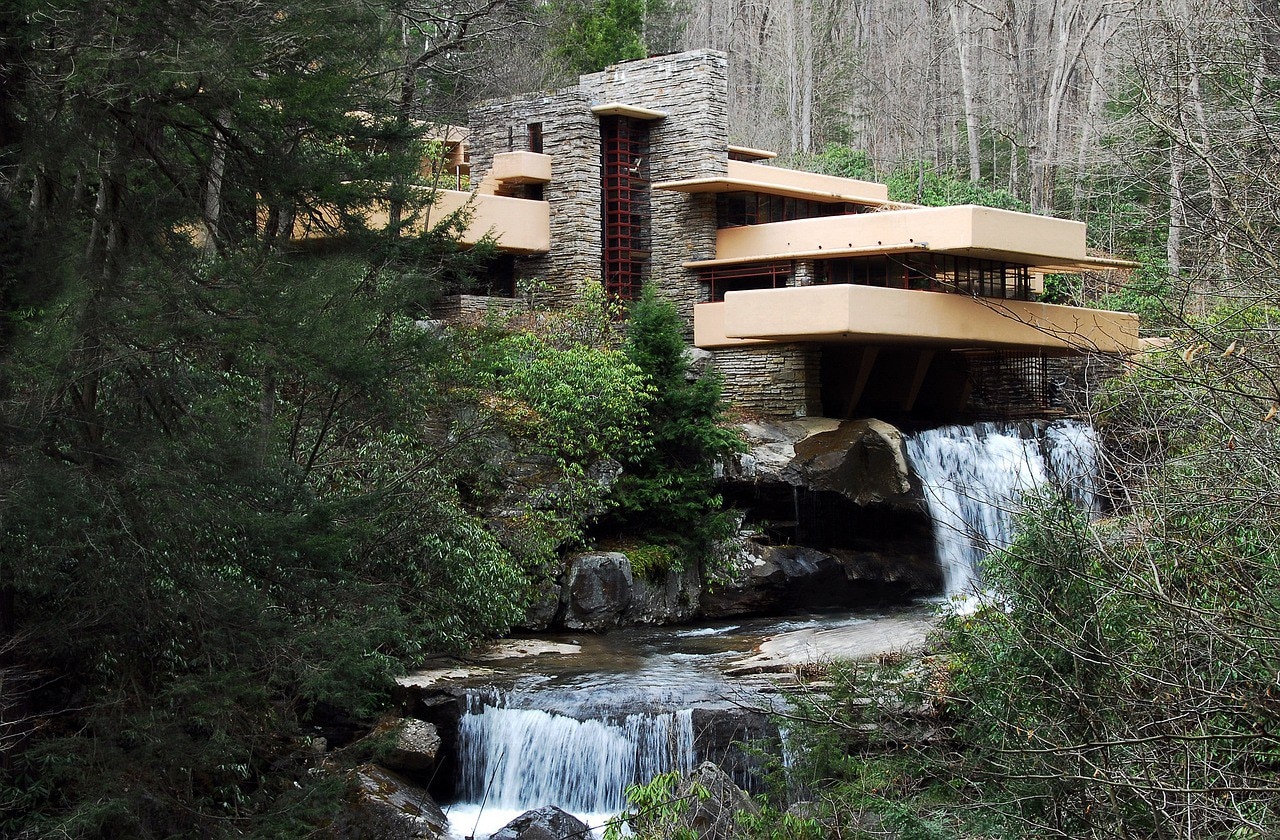

• Neutra did dig the foundations and managed to leave just before they were ordered to halt construction as a result of shortages of materials during the war. Sign up for our newsletter to get unique arts & culture stories and videos from across Southern California in your inbox. Personalize your stream and start following your favorite authors, offices and users. 10 years after the design of Fallingwater by Frank Lloyd Wright in Bear Run, Pennsylvania, the Kaufmann’s were looking for a residence that could be used to escape the cold winters of the northeast, which would primarily be used during January.

Barbie Movie Filming Locations in California - Write For California

Barbie Movie Filming Locations in California.

Posted: Mon, 17 Jul 2023 07:00:00 GMT [source]

In 1946 Edgar Kaufmann commissioned Richard Neutra to design a winter vacation home in Palms Springs, California. A decade earlier, he hired Frank Lloyd Wright to design his renowned Fallingwater house. However, while still an enthusiast of Wright’s work, Edgar wanted a lighter feeling than their Fallingwater home and felt Neutra could deliver. The gloriette, a serene outdoor room above the house, was Richard Neutra’s creative way of bypassing zoning codes that forbade two-story structures. Richard Joseph Neutra (/ˈnɔɪtrə/ NOI-tra;[1] April 8, 1892 – April 16, 1970) was an Austrian-American architect.

The house underwent “an award-winning restoration” by Marmol Radziner in the 1990s that included the installation of air conditioning. Neutra promised to preserve the spirit of the extant villages, but there was no way to accommodate more than three thousand units without resorting to high-rises. Neutra wrote, “The tall buildings here will be spaced great distances apart and in spacious groups, separated by several valleys.” It’s doubtful whether families on the thirteenth floor would have felt nature’s embrace in any real sense.

SAH Archipedia tells the story of the United States through its buildings, landscapes, and cities. This freely available resource empowers the public with authoritative knowledge that deepens their understanding and appreciation of the built environment. Richard Neutra’s Kaufmann House in Palm Springs was designed and built in 1946–1947, although some sources claim that the preparatory contact between client and architect occurred in 1945. The house exemplifies Neutra’s approach to designing a house and its surroundings as a single, continuous environment, a concept he had begun to work with in the early 1940s. Other examples are Neutra’s Nesbitt House (1942, Los Angeles) and the Tremaine House (1945–1948, Montecito). The Kaufmann House is an early example, and one of the clearest, of a post–World War II southern Californian modernism that closely integrates the building with its environment.

In 1921, he served briefly as city architect in the German town of Luckenwalde, and later in the same year he joined the office of Erich Mendelsohn in Berlin. Neutra contributed to the firm's competition entry for a new commercial center for Haifa, Palestine (1922), and to the Zehlendorf housing project in Berlin (1923).[10] He married Dione Niedermann, the daughter of an architect, in 1922. They had three sons, Frank L (1924–2008), Dion (1926–2019), who became an architect and his father's partner, and Raymond Richard Neutra (1939–), a physician and environmental epidemiologist. The Harrises purchased the home for US$1.5 million, then sought to restore the home to its original design.

As photography became more available, magazines, publications, and printed media became the primary way people would consume architecture. Neutra’s work is notable for its ability to blur the boundary between inside and outside. In the Kaufmann House, this is done with walls that run from the interior to the exterior clad in the same stone material. This technique allows the eye to travel from the inside to the outside with minimal interruption, visually connecting the two spaces. It wasn’t until 1993, when Brent and Beth Harris, a financial executive and an architectural historian, moved in that there was an attempt to bring the Neutra house back to its original splendor piece by piece. After World War I, Neutra moved to Switzerland, where he worked with the landscape architect Gustav Ammann.

The Oliver House, a few streets over, contains what might be the world’s most vertiginous breakfast nook, hanging over the yard at a diagonal to the street. The astounding Kallis House, in the Hollywood Hills, has walls that bend in and out, like an accordion. Modernist rhetoric notwithstanding, there’s a residual Romantic streak in Schindler’s buildings. As Todd Cronan notes, in a forthcoming book on California modernism, they retain an unmistakable sculptural quality.

Prefabricated steel girders were assembled in less than forty work hours; the spraying of the concrete skin was accomplished in two days. In the end, though, the industrial might of the building may have detracted from its livability. The Lovells later complained that it had “no lilt, no happiness, no joy.” The house has experienced wear and tear in recent years, and needs a thorough restoration. The art-world potentates Iwan and Manuela Wirth are buying the property, with plans to bring back its original lustre. The Fredrick Robie House, located in the Chicago neighborhood of Hyde Park, is one of the most iconic examples of modernist architecture. Designed by renowned architect Frank Lloyd Wright in 1909, the house has been called "the most important building of the twentieth century" and "the greatest work of architecture America has produced."

Neutra named this elevated room a “gloriette,” a northern European Baroque term that denotes an elevated pavilion offering views of a garden or a landscape. Although Neutra enjoyed fame from the thirties onward—in 1949, he appeared on the cover of Time—clients of relatively modest means could still afford to hire him. (Several of the Neutra Colony houses were first owned by Japanese American families whose members had been in internment camps during the Second World War.) Those economics are long gone. Amid a prolonged vogue for mid-century modernism, Neutras go for extravagant prices. The Kaufmann House, a Palm Springs idyll that Neutra built for the department-store owner Edgar J. Kaufmann—who also commissioned Frank Lloyd Wright’s Fallingwater—is on the market for $16.95 million.

Neutra wandered around the area, making sketches and interviewing the residents. This was always his point of departure, Alexander later said—“not looking at maps first but looking at the people.” In a memorandum, Neutra expressed admiration for the community that the villagers had built. It was, he wrote, “the loveliest slum in the most charming setting which the country can boast.” His use of “slum” showed that, despite his sympathetic slant, he adhered to the paternalistic mentality of mid-century urban planning. Their first address was 835 Kings Road, in West Hollywood—a communal dwelling that Schindler had built in 1922, and that he shared with his wife, the writer and educator Pauline Gibling Schindler. The core structure consists of exposed concrete walls that gently lean inward, like the sides of a tall tent. Indeed, the design was partly inspired by a camping trip to Yosemite that the Schindlers had taken in 1921.

No comments:

Post a Comment